Whistlers: 박보나

-

휘휘파파 phwee phwee fweet fweet, 2024, 4K video with sound, 22’52”

휘휘파파 phwee phwee fweet fweet, 2024, 4K video with sound, 22’52” -

Gallery Chosun hosts Bona Park's solo exhibition, ≪Whistlers≫ from 2 August to 22 September 2024. Bona Park, who has written and worked on the boundary between art and life, and on labor in art will explore friendship among women in the exhibition. The friendship she refers to means support and solidarity between women.

≪Whistlers≫ started through an association with WING, an organization supporting the resilience of women exiting prostitution. Established in 1953 to care for war orphans and widows, WING has been supporting women who have left the sex trade and those who have suffered violence since 1996. Since Park happened to read an interview of the CEO of the organization and wrote about them, she has been connected to them by eating meals together and conducting workshops. Park explains that ≪Whistlers ≫ has to do not with an “outside” that is separate from her but with an “outside” that is part of her which blossoms as friendship with women.

Whistlers (2023), which shares the same title as the exhibition, is a video work that Park produced at a WING workshop with the women last year. It shows a performance of serial whistling, as 12 women standing side-by-side take turns inhaling and exhaling each other’s breaths. Sharing breath turns into a poem, and it gets embroidered on t-shirts donated by the artist’s friends in How to Whistle (2024). phwee phwee fweet fweet (2024) is a video work in which two actors read six letters that Park’s friends including actors wrote to their friends, whispering an emotional intimacy that transcends language and logic. This intimacy continues in Mountains (2024), where participants at the 2023 WING workshop depicted what they cherished, held in their hands.

Many of Park's works and projects question social systems, including art, economy and history by uncovering the various structures and labors therein. By juxtaposing art with social conditions, her practice creates awkward situations that confuse and upend the boundary between art and daily life. The box in a plastic bag (La boîte - en - sac plastique) (2010) is a performance in which the participating artists and museum staff who contributed for making exhibitions at the private view carry around plastic bags of groceries their usual dinner habits. In I tell what you believe 1(2013) is her performance in which invigilators walk in the museum, wearing tap dance shoes written 'I tell what you believe' throughout the exhibition, making cracking noises in the museum. She has also collaborated with foley artists who work behind cameras to produce images. Through these works, Park blurred the boundary between art and life and highlighted labor and collaboration in art, which led to uncomfortable questions about the system.Bona Park's solo exhibition, ≪Friends≫ in Gallery Chosun in 2013 focused on the people she collaborated with, such as a performer for playing piano and a shoe-shiner who shone her shoes for the opening. On the other hand, the exhibition, ≪Whistlers≫ in 2024 is more about the trust, friendship, and intimacy that emerge through the process of collaboration.

-

-

Bona Park’s Whistlers: Friendship as a Form of Exhibition, Collaboration as a Form of Friendship

to be with oneself in the other -G.W.F. Hegel, Phenomenology of Spirit

Have you ever laid a dinner out for someone? Bona Park’s solo exhibition Whistlers began from the artist’s connection with an organization entitled WING, which works to support the resilience of women exiting prostitution. After the artist happened to discover an interview with the organization’s CEO Jungeun Choi—who explained human self-sufficiency and rehabilitation in terms of “commitment to cooking and eating your own meals”—she took the idea of the dinner table as a site of rapport and healing and transported it into the realm of art. Within the larger discourses of contemporary art, including global crises and various contemporary issues, Park creates a small dinner table for us to share in. In place of “discourse” that broadens critical horizons, she holds out “friendship” as a way of filling our bellies. These dinner tables as spaces of intimacy center on a form of women’s practice with a deep place in the artist’s heart, conveying a message of solidarity through the layering of close connections and future encounters with her longstanding collaborators.Bona Park and I have known each other for some time, following one of her solo exhibitions in 2007 as well as an artist-critic matching activity in 2016. We have shared our thoughts over major and minor issues relating to each other’s art and life. I have sometimes invited her over and made meals for her; these days, we often walk our dogs together. We have occasionally gone to see performances together, followed by exchanges of incisive opinions on the way home. Our text exchanges would continue to the next day and the day after that, with the process becoming a familiar part of our ways of thinking as we resolved needless misunderstandings and preconceptions: “A friend of mine is coming over for dinner. Care to join us?” These experiences of occasional togetherness, of embracing and easing, would sometimes end up leading me to unexpected places. Can I describe this as a new stage in the curator and artist’s progression toward an exhibition? Or as a chance companionship forged by two people? It is an ambiguous relationship, neither this nor yet—yet also something obvious. Perhaps I can refer to it as a form of “cultural intimacy” or “intimacy solidarity,” rather than a conceptual collaboration or rational partnership.

Over the course of our lives, we experience friendship with different counterparts in different ways. Those counterparts may include siblings, members of the same or opposite sex, pets, plants, objects, and even works of literature and art such as books. In some cases, we may sense an undeniable intimacy or identification with artists or thinkers who have already passed into the phantom realm (for me, Virginia Woolf is such a case). Through the experience of one story leading into another, through mutual reliance and entrusting and acceptance, through the thicknesses and weights from repeated reading and re-reading, we gain comfort, we learn, we grow, and we stand on our feet again. Even amid the social isolation of the past few years—now a part of our past—we human beings readily adopted unfamiliar technological media and sought news from the people close to it, if only via remote. It may be that this sense of belonging based on emotional bonds represents the minimal unconditional solidarity that must be sustained for us to survive as humans.

For a long time, women were regarded as passive objects rather than active subjects. As a result, we have been left out of the many contemplations of friendship referred to in our history—the friendships that can be found in the texts of thinkers like Aristotle, Montaigne, Blanchot, Levinas, Foucault, Deleuze, or Derrida. This may explain why even today, friendships among men are taken for granted while friendships among women are regarded negatively. I also own collected letters by various writers who shared friendships: letters between Albert Camus and Jean Grenier, letters between Natsume Soseki and Masaoka Shiki, Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet, and Vincent van Gogh’s letters to his brother Theo. In the process, I have found myself connecting with artistic lives during those eras through the reverberations of truth associated with the letter format. Here, too, the records are all by men. It may be that women ended up alienated from the male province of friendship because of their long exclusion as active subjects; perhaps they were concealed outside or beneath friendship, never achieving proper documentation or definition. It may be that friendships among women are a new kind of relationship that we will need to rediscover going forward—or an old friend that we should reconnect with at once.

Is there truly a difference between male and female friendships? In contrast with the “solemn vows” forged under the hegemonic systems that men have been bound to uphold, friendships between women have existed in a realm closer to hidden emotions, highly subjective and fleeting: the endless choices that came with the vicissitudes of life, and the resulting realizations, mistakes, new desires, and disappointments. Céline Condorelli is an artist whose works straddle the realms of art and architecture, as well as a researcher who considers friendship in terms of the basic politics of alliance and responsibility; in “Too Close to See: Notes on Friendship,” she and the philosopher/theorist Johan Frederik Hartle engage in a dialogue on friendship as a productive concept. A few days ago, I was reading through a book that included that text, and I happened to see an underlined sentence, in which Hartle quoted some sentences from the 25-year correspondence between Hannah Arendt and her friend Mary McCarthy: “‘It’s not that we think so much alike, but that we do this thinking-business for and with each other.”[1] The message that the “thinking-business” itself can be an effort for friendship’s sake—and that friendship can accordingly be a prerequisite for work—suggests a different direction for collaboration to those of us working in the realm of art. As these words indicate, the most sublime potential within friendship lies in the things developed together by the intellects of colleagues.

Isn’t “friendship” a romantic notion? Not at all. Operating outside or on the fringes of art for art’s sake, Bona Park had explored the back sides, undersides, and surroundings[2] of ideologically standardized images. Yet she does not present the sort of conceptual art that challenges the system and critiques the ideas of “ownership” or “authorship” of an artwork. Instead, she observes the situations that take shape in the process of working with collaborators in their own realm, as she creates narratives that are original and even extraordinary. The creative process of two or more different individuals working together is so subjective—yet so fleeting and intimate—that it tends to evaporate into words like “labor,” “Other,” and “collaboration” before we even sense it (while remaining inscribed indelibly inside us). As Bona Park embraces these special circumstances, friendship becomes an alternative method or creation or an attitude for achieving a more equitable world: “Friendship is no longer something distinct from labor, but something that sets down roots as ‘emotional labor’ within a shared process of mutual production.”[3]

In the artwork presented at Bona Park’s solo exhibition Whistlers, there are no contracting and contracted parties, no victims and protectors, no experts and non-experts, no art and non-art. Instead, there is the welcoming, trust, solidarity, friendship, intimacy, and tenderness that bridge the gap, lingering briefly as an “ad hoc driving force.” Park uses that shared place to begin a friendly manifesto aimed at shifting from the lives of others as art to the living truth within the lives of others. The lips of the female WING members passing whistles to each other, the ears of actors whispering out letters, the hands of the unseen artist sewing one stitch at a time—the warmth they share causes our own lips to purse, our own ears to perk up, our own fingers to move. As I look back on the last few years of us opening up each other’s worlds—becoming sources of thought for one another as artists, curators, and individuals—I feel that if time spent together can become a process of collaboration, and if the friendship created with that can produce something in the form of an exhibition, perhaps this exhibition is opening up that possibility. That may be the whistle that Whistlers shares.

by Enna Bae

[1] Between Friends: The Correspondence of Hannah Arendt and Mary McCarthy, 1949–1975. Carol Brightman, ed., Harcourt Brace, 1995

[2] Rey Chow, Writing Diaspora. Tactics of Intervention in Contemporary Cultural Studies, Korean trans. Suhyeon Jang & Uhyeon Kim, Isan, 2005, p. 53.

[3] Stine Hebert & Anne Szefer Karlsen (eds.), Self-Organised, Korean trans. Gahee Park, Hyogyoung Jeon & Eunbi Cho, Mediabus, 2016, p. 90.

-

Whistlers

-

Past exhibition

-

external exhibition

-

The 2012 New Museum Triennial, 'The Ungovernables', New Museum, New York, USA봉지 속 상자 (La boîte - en - sac plastique) 2012 2012 The 2012 New Museum Triennial, 'The Ungovernables', New Museum, New York, USA -

2014 아트스펙트럼 2014, 삼성리움미술관, 서울, 한국당신이 믿고 있는 것을 말해드립니다 1, 2014 -

Domestic-scale choreography 2, 2015 -

코타키나 블루 1, 20152015 코타키나 블루 , 신도리코 본사 문화 공간 , 서울 , 한국 -

태즈메이니아 호랑이, 20182018 성좌의 변증법 : 소멸과 댄스 플로어 , 플랫폼엘 , 서울 , 한국 -

봉지 속 상자 (La boîte - en - sac plastique) 서울카트 버전 / 서울 버전 , 2020 (2020 모두를 위한 미술관 , 개를 위한 미술관 , 국립현대미술관 , 서울 , 한국

-

-

Publications

-

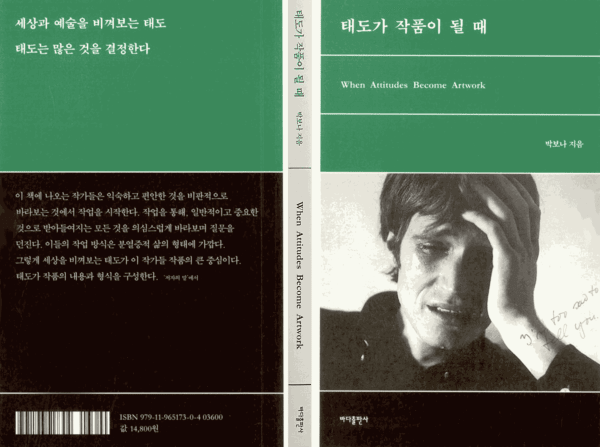

태도가 작품이 될 때 : When Attitudes Bocome Artwork

박보나Bona Park is a visual artist working across video, sound, installation and performance. Her performative works move beyond traditional art forms, offering audiences new ways of experiencing art. 『When Attitude... -

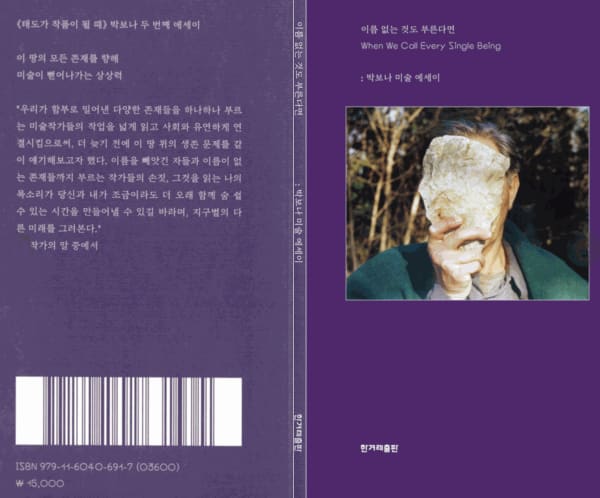

이름 없는 것도 부른다면 : When We Call Every Single Being

박보나『When We Call Every Single Being』 is Bona Park’s second art essay, centered on the theme of life. The essay challenges the common idea that contemporary art is difficult to... -

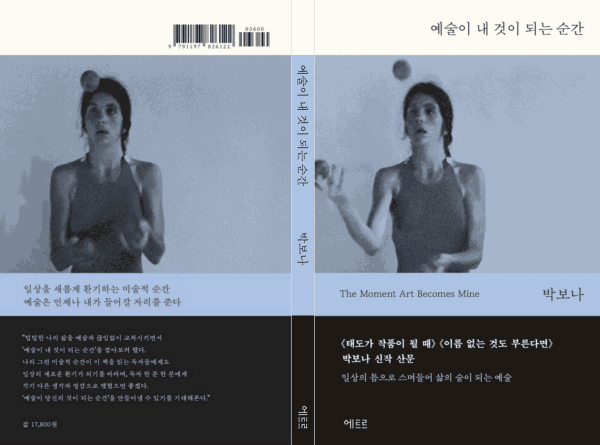

예술이 내 것이 되는 순간 : The Moment Art Becomes Mine

박보나Bona Park’s latest essay, 『The Moment Art Becomes Mine』 , explores the interplay between everyday life and art. Moving freely across the boundary between the two, she unravels thoughts and...

-